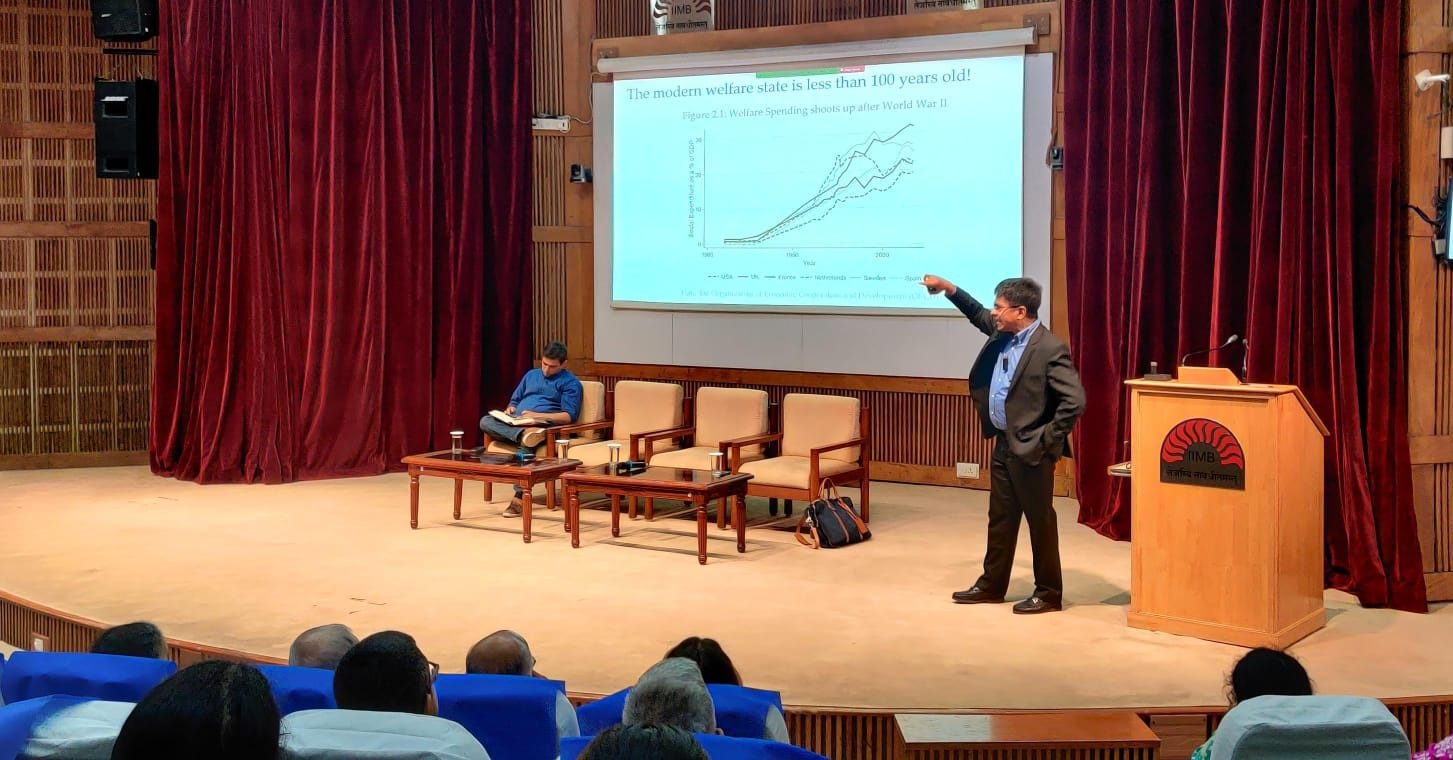

I finished reading Accelerating India’s Development by Karthik Muralidharan this week. I had been waiting for the book since Karthik Muralidharan appeared in Amit Verma’s podcast for the first time. I ordered it as soon as it was released. But it took me almost a year to complete this masterpiece of a book. Although the time it took is a reflection of my procrastination skills, it is also due to the density of high-quality content in the book—even the notes and references run to almost 200 pages. Every chapter is rich with fresh perspectives and creative, yet practical, recommendations for India.

In this article, I would like to summarise some of the ideas that stood out to me. All these ideas, and the entire book, revolve around one major concept: the importance of building state capacity in India.

1. Indian State & Service Delivery

The Indian state fails in effective service delivery. While we have schemes and institutions, the delivery of services fails to reach all citizens. For example, while we have schools across the country, not all schools have teachers who are available for the students. While we have courts, more than 50 million cases are pending in Indian courts. While we have health clinics and hospitals across the country, they face high amounts of staff absence.

A core argument of the book is that India’s weakness in service delivery reflects inadequate investments in state capacity. State capacity is the ability of the state to design and implement its own policies effectively. Improving state capacity involves enhancing the skills of government personnel, collecting and analysing data to improve the state’s functioning, improving the quality of tax collection and government expenditure, optimising tasks and incentives across government layers, etc.

According to Karthik Muralidharan, the Indian state’s weak state capacity is not surprising given the expectations on it. Most Western democracies with better state capacity had very low expectations of themselves when they began. In these countries, the right to vote was not initially available to all citizens. In those years, the state has had the opportunity to develop its capacity. As the franchise expanded over time to cover more citizens, the state could gradually increase its capacity to meet growing expectations.

Unlike these countries, the Indian state started with universal franchise in 1947 itself. While this is politically and socially just, it placed immense pressure of expectations on an infant state. It is commendable that the Indian state has not crumbled yet. But according to Muralidharan, it is time for us to make investments in state capacity to meet the basic needs of all citizens.

Interestingly, there are other voices in the policy field who agree with Muralidharan’s diagnosis of the Indian state’s weak capacity, but disagree on the solution. While Muralidharan advocates for efforts to build state capacity, people like Shruti Rajagopalan find this counterproductive. How can a weak state build its own capacity, they ask. In a weak state like India, efforts to build state capacity might only add more pressure on the existing capacity. Instead, they suggest simplifying the rules and responsibilities of the state, so that it can first perform essential functions effectively. Then the rules can gradually become more complex, as the state grows in capacity.

2. Efficiency vs Equity Debate

The book also delves into the Sen-Bhagwati debate, which is an ongoing policy debate in India, represented by Amartya Sen on one side and Jagdish Bhagwati on the other. People who side with Sen push for human development as a priority over economic growth. They point towards places like Kerala, Vietnam, and Sri Lanka, which have achieved high human development at modest levels of per-capita income.

The Bhagwati side of the debate vouches for economic growth through better infrastructure, law and order, and free markets. Human development comes as a by-product. They point at Western countries and their earlier years as the model. People like Lant Pritchett have also pointed to the value of this view, where he says, “economic growth is enough, and only economic growth is enough” for everything, including basic human development.

According to Muralidharan, this debate is not useful for India. He says that it is a fact that governments spend considerable amounts on physical infrastructure and social sector anyway. The problem India faces is that public money is spent badly, regardless of where it is spent, and this is what needs to change. While Muralidharan says that free markets and growth are essential for efficiency, social sector investments in human development cannot be ignored in a country like India. He says:

“....Hence, the best solution is for the state to allow well-regulated competitive markets to function freely to maximise efficiency, while the state focuses on providing essential public services and well-designed welfare programmes to promote equity.”

3. Local Volunteers to Improve Education and Health Sectors

Muralidharan analyses various sectors of the Indian economy in the book. He gives many practical and creative suggestions for them. One of the suggestions that stood out to me was the advantages of engaging contractual or volunteer staff in the education and health sectors.

In education, India faces a crisis in terms of learning outcomes. Average learning levels, especially in government schools, are substantially below grade-appropriate standards. We have previously written as to how such a similar problem exists among tribal students of Kerala.

One of the ways to address this is to improve the teachers. Traditionally, this is done by increasing the salary of teachers or hiring more ‘qualified’ teachers. Muralidharan points to research that shows the value of locally-hired volunteers, who have completed only 10th or 12th class, in improving basic literacy and numeracy. Hence, he proposes implementing a volunteer-led after-school program to improve foundational literacy and numeracy for students, like the Illam Thedi Kalvi programme in Tamil Nadu.

Similarly, in the health sector, the rural areas face substantial staff absenteeism. Muralidharan suggests tackling this through hiring and training local staff in basic medical skills to plug this gap.

Fiscal pressures and efficiency requirements have driven the government to hire a large number of contractual staff in recent years. Muralidharan demonstrates that hiring local contractual staff or volunteers can help address many of the last-mile delivery issues in the education and healthcare sectors, provided it is done strategically.

Finally..

I believe Karthik Muralidharan’s book is one of the best works for anyone interested in development and policy in India. If you don’t have the time to read the book, here is an (imperfect) summary I made while reading the book.

Overall, weak state capacity is one of the major reasons for the failures of the Indian state. There is an immediate need to address the state capacity issue. This book makes a significant contribution towards this discussion.