Gaps in Kerala's Tribal Education

Analysing the challenges in the tribal education system of Kerala and the policies at play

From the tribal hamlet of Galasi in Attappady, one has to walk more than two hours through the thick Silent Valley Forest to reach the nearest road. Reaching the nearest higher secondary school by vehicle takes another hour. Most students from the region have to endure such hardships to attend school or live in hostels from a young age. Despite the efforts made by students to commute for education, our education system ultimately fails them.

One of us (Anand) has worked in Attappady for the past three years, gaining a firsthand understanding of the challenges faced. The region is one of Kerala's most backward areas and is inhabited mostly by tribal communities. This experience has allowed us to rethink some of the educational paradigms in tribal education.

Tribal Non-Tribal Divide

The tribal population in Kerala is close to 1.5% of the total population. They are mainly concentrated in the Wayanad, Idukki, Palakkad, Kasaragod, and Kannur districts. Emerging from historical disadvantages, the community has yet to fully benefit from the advancements made by the rest of society in terms of education and economic growth.

Regarding education among tribal communities, let's consider some critical numbers. According to the Economic Review 2023 released by the State Planning Board, the pass percentage for the ST community in Kerala at the 12th standard level was an abysmal 58.60%, compared to the overall pass percentage of 82.92%. The B.Tech pass percentage for tribal students was 24.56%, while the total pass percentage was 56.14%.

A large number of tribal students attending schools and colleges are either failing or dropping out. Is this because tribal and marginalised students are less capable? Evidence suggests that the capabilities of tribal students are on par with or even exceed those of other students. Their low achievement levels can be attributed to certain school-related factors. We must now ask how our education policy and system create the divide between tribal and non-tribal students.

Failures in the Education System

To begin with, tribal education mirrors all the failures of our education system in general - these include a filtration-based approach, rote learning, and issues with teacher incentives.

In his essay "Reforming the Indian School Education System", economist Karthik Muralidharan argues that the Indian education system performs a sorting or filtration function. The system rewards high-performing students and selects them for higher education and employment, while the low performers are left behind.

Moreover, the curriculum followed in our schools is vast, requiring students to learn a lot of information. Added to this, we also give undue significance to examinations. This naturally favours rote learning. The human development role of education, where the abilities and skills of students are developed, is generally not emphasised.

This impacts teacher incentives. The large syllabus and the excessive importance of examinations incentivize teachers to finish the syllabus within the stipulated time and make students exam-ready. The focus of the system, therefore, is solely on examinations and not on learning and understanding.

Another major problem plaguing our education sector is the lack of foundational literacy and numeracy skills. The annual ASER report released by Pratham highlights some worrying statistics. For example, as per ASER 2023, only 57.3% of students aged 14-18 can read basic sentences in English. This implies nearly half the students lack basic reading abilities, impacting their understanding of other subjects too. This issue becomes evident in higher classes, but by this time, students may have lost interest in education and would be relying solely on rote learning. Some would have already dropped out.

Case of Tribal Education in Kerala

Along with other failures in the education sector, the lack of foundational literacy and numeracy skills is particularly evident among tribal students. In a survey conducted by Nayaneethi Policy Collective for classes 3 to 8 in a tribal school in Kerala, some concerning findings emerged:

44.3% of students could not read basic sentences in Malayalam, the language of instruction.

70.34% of students could not read basic words in English.

81.01% of students could not do simple subtraction and division in Mathematics.

Evidently, there is a learning problem among tribal students in Kerala that may have emerged due to a combination of factors.

The first and most significant aspect may be the historic disadvantages the community has faced. Tribal students who attend schools today are likely to be first-generation learners or have parents who cannot support them in education. Second, tribal communities in Kerala have different mother tongues, while Malayalam, which is often the medium of instruction in schools, is an unfamiliar language for them.

It is also important to understand the impact of COVID-19 lockdowns. While the Government of Kerala conducted digital classes during the lockdowns, these did not effectively reach remote tribal hamlets. Even if the classes had reached all beneficiaries, they would only have benefited students who already possess foundational skills.

In such a scenario, how do we reform tribal education in the state?

Reforming Tribal Education

First, to gauge the extent of the learning challenge, the Government of Kerala needs to conduct a study on learning outcomes in schools, particularly among tribal students. Following this, interventions to tackle the learning gaps must be instituted within the curriculum, such as teaching at the right level.

Second, at a policy level, our education system needs to be more considerate of the unique challenges faced by tribal students. Research shows that teaching in mother tongues is essential for cognitive development and improving learning outcomes. In primary classes, the language of instruction for tribal students should be in their mother tongues with content that reflects their local contexts. Malayalam and English can gradually be introduced.

Third, the government should revisit the current system of alienating tribal students in dedicated tribal schools until class 12. This reduces their exposure to the larger society, affecting their post-school studies and ability to cope with a diverse student pool in colleges. Such exclusive tribal schools should be limited to primary sections following which students can gradually be integrated into schools with non-tribal students.

Fourth, there is a need for teachers to be sensitive to the socio-cultural factors at play. Teachers need to spend more time with tribal students and provide them with support that they may not be receiving at home. Considering the extra work that teachers would have to put in, a proportional increase in salary structures for teachers handling tribal students can be considered. This will also attract talented teachers to contribute to tribal education.

Education for Social Change

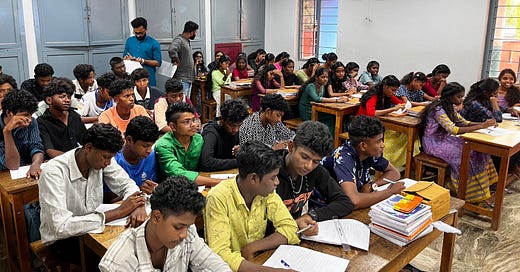

Kerala, with its robust educational infrastructure, has performed well compared to other states in India. However, over the years, it has overlooked its marginalised and tribal communities. For education to truly be a tool for social change, we need to ensure that all our students can use it effectively. We cannot squander the efforts of our tribal students who undergo immense struggles just to be in a classroom.

A Note for Readers:

To read our previous article on the NEET exam issue, visit The NEET Conundrum.