Kerala has the Foundations, Now it Should Build its Economy

Understanding why Kerala's socio-political foundations have not created economic growth while suggesting policy measures that needs to be implemented

Kerala’s story of social development is well documented and is considered to be a model within India. With top rankings in literacy, public health, gender indicators, and decentralized governance, it has a reputation for being socially progressive and institutionally strong. Kerala has a well-functioning Panchayati Raj system that conducts regular elections, an engaged citizenry, and responsive politics. From Kudumbashree to community health programs, Kerala has demonstrated the possibilities that open up when the state and society work together.

But despite these achievements, Kerala’s economy remains weak. Studies and data over the years point to a declining share in national GDP, large debts, unemployment, and struggling manufacturing industries. As the state now enters a phase of demographic ageing, the need to confront this paradox between social and economic development is becoming more urgent.

Strong and Citizen-Centric Institutions

Strong institutions are important foundations in generating growth, and Kerala’s socio-political institutions are among the best in the country. It ranks second in the Devolution Index released by the Ministry of Panchayati Raj, topping parameters such as elections, financial autonomy, and administrative capacity.

Devolution Index of Panchayats in Indian States - Source: Ministry of Panchayati Raj

The People’s Planning programme in Kerala has been institutionalised for close to three decades now. This has allowed for reforms to come up from the society rather than being implemented in a top-down system. The State Planning Board, supported by District Planning Committees, has a planning and funding system that allows local bodies to have their own budgets and development strategies.

Kerala’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic is an example. It was swift, coordinated, and grounded in local action. The system worked because of Kerala’s strong institutional capabilities at the grassroots.

So why has this strong institutional foundation not translated into robust economic growth?

Weak Economic System

Kerala’s economic system was traditionally dependent on agriculture, which later declined due to land fragmentation, rising labour costs, and outmigration. From the 1970s onwards, a large part of the economic system was sustained by remittances flowing into Kerala from migrants in West Asian countries.

While the remittances supported public revenue to an extent, there was no real growth in the industrial sector. The policies of regulating private industries across India were an equal factor in this, and the situation in Kerala follows the pattern observed across the country. But in Kerala, the labour movement exacerbated the situation.

Later, Kerala transitioned to a service-driven economy. As per 2023-24 data from the Economic Review 2024, the services sector contributes 64.25% to the total Gross Value Added (GVA) and had 48.53% employment. This is far higher than the rates for India, which are 54.61% share of services in GVA and 29.73% employment.

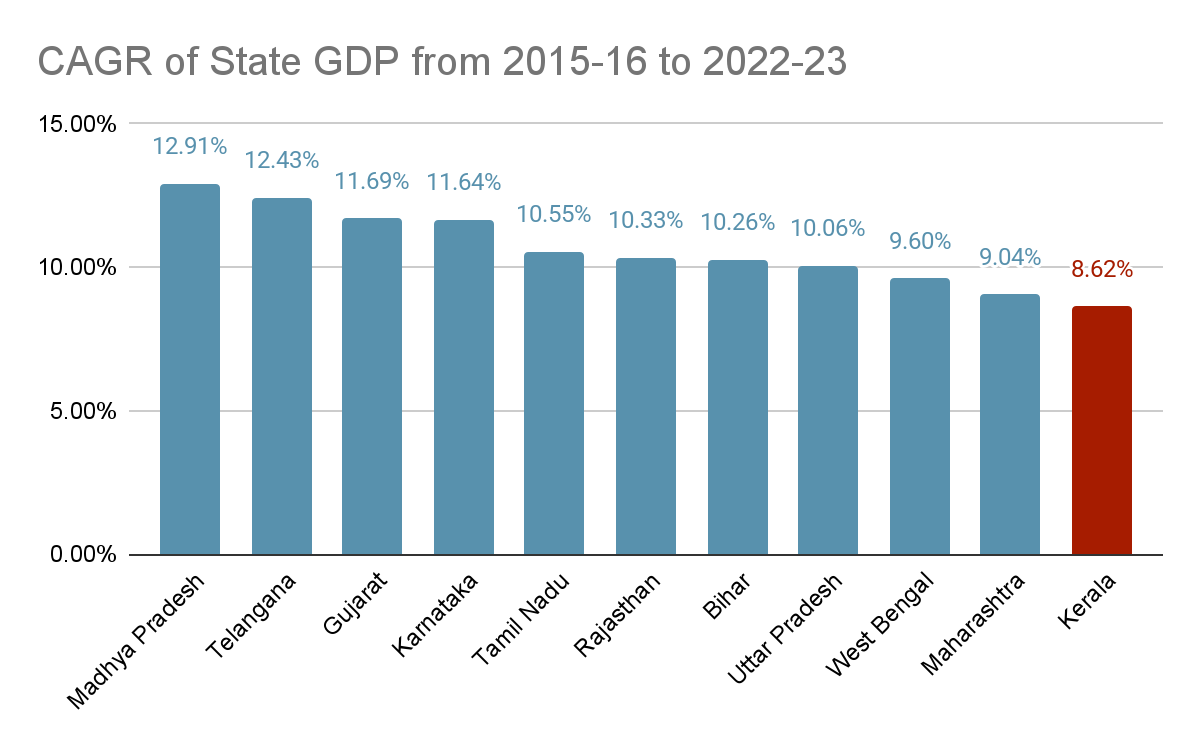

This economic system, though, has not created enough growth in the economy. Considering the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of Kerala’s GDP from 2015-16 to 2022-23 (see graph below), Kerala is one of the least growing states in the country.

Source: Economic Survey 2024-25

Part of the problem has also been Kerala’s reliance on redistribution policies at the expense of wealth creation. The policies in the state considered dignity, access, and public services as important, but under-emphasised productivity, entrepreneurship, and investment. But you need wealth to be generated before it can be redistributed. Without entrepreneurship and industries creating wealth, there is nothing to be redistributed. This has created an imbalance where welfare demands keep on increasing, but there are limited funds to meet these demands.

Remittances from West Asia have masked this imbalance in the past. For decades, the remittances allowed for household consumption and public revenue to build. But this model has reached a saturation point. Gulf economies are diversifying, and Kerala’s migrants are settling down with families in their host countries with minimal remittances back to the state. With remittances reaching a low point and redistribution policies continuing, the system is becoming more unsustainable with time.

To meet the growing obligations, the state needs to grow. And growth requires a shift in economic policies.

A New Growth Strategy

Despite its strong socio-political institutions, Kerala does not have a strong industrial or entrepreneurial ecosystem. This calls for a change in the economic strategy. For entrepreneurs and industries to thrive, there should be availability of labour, land, and capital, along with a culture that encourages risk-taking.

Labour laws in the state remain rigid. Strikes and shutdowns are frequent, often leading to the closure of industries. The perception of Kerala being a difficult place to do business persists.

But in the past few years, the state Government has been vocal about growing more industries. This is supported by projects such as the Vizhinjam port (the first transshipment hub in the nation), which is expected to spur industrial growth.

To support this strategy, there is also a need for Kerala to chart a new growth path. To begin with, the state needs to liberalise labour laws and encourage private sector participation in the economy. An entrepreneur today faces numerous regulatory problems, labour disputes, and license requirements. This is in addition to the large risks they already take to start an enterprise. Easing these regulations for a would-be entrepreneur is critical for more industries to come.

Secondly, Kerala’s land use policy has been stringent. It is difficult to lease land for businesses, and converting agricultural land is nearly impossible. This prevents land from being used to its highest value. For example, because of land use laws, even when a farmer generates minimal profits or employment prospects from their land, they cannot sell it to an industry that might have been profitable. There is a need to ease land use policies to allow more freedom in how land can be used. This will help create more value out of Kerala’s already constrained land.

Thirdly, there is a need to encourage sectors where Kerala has a comparative advantage, such as healthcare, tourism, marine technology, and food processing. Exclusive investment zones, tax breaks, and deregulations in these sectors will help increase investment.

Lastly, Kerala’s policy of building a knowledge economy is welcome. But it needs to develop clusters of research, industries, and human resources and create avenues where all these elements interact. From Silicon Valley to Bangalore, such knowledge clusters are found to be important to drive innovation. These cluster formations should be critical elements in the knowledge economy mission.

Conclusion

Kerala’s model in the socio-political space showed the possibilities of progressive politics, strong institutions, and people-centric governance. Now it must replicate this in the economic space.

Kerala is ageing. Remittances are flattening. The youth are migrating out. Kerala can utilize its institutions, human capital, and socio-political strength to create rapid growth if it rethinks its economic policies. Kerala indeed has a strong foundation, and the time is indeed ripe to make a change.

A thought provoking analysis of how the economy and welfare are interrelated.